Shaping Stoneware: The Ceramic Forms of Claude Conover

Published for Wright Auction House, October 28, 2021

by Glenn Adamson

Revolution or resolution? In modern ceramics, the former gets most of the acclaim. The disciplinary rupture brought about in the 1950s by Peter Voulkos in California, and by comparable figures in other parts of the world, was a paradigm shift, to be sure. But it wasn’t all that was happening. There were other, equally vital currents flowing through ceramics at midcentury, less explicitly avant-garde, but equally rooted in modernism.

Claude Conover deserves recognition as one of these alternative protagonists. In many respects, he was the direct antithesis of Voulkos. Based in the Midwest rather than America’s “left coast,” he went about his work with quiet professionalism. Voulkos’s work was disjunctive, built from typical pot-shapes like slabs and thrown cylinders but piled up in highly experimental configurations. Conover’s vessels are sublime in their coherence, constructed in a totally unconventional way that somewhat disguises its own innovativeness. Even their biographies crisscross: Voulkos was a skilled potter who battered his way into sculpture through sheer force of will, while Conover initially trained as a sculptor and found himself making pots almost by chance.

Claude Conover was born in Pittsburgh, in 1907, and grew up nearby in New Castle, Pennsylvania. He attended the Cleveland School of Art, studying both painting and sculpture, and graduated in 1929. (The designer Viktor Schreckengost, whose Jazz Bowl of 1930 is the best-known example of American Art Deco ceramics, was a classmate.) For the next three decades, apart from a period of war work in the early 1940s, Conover had a successful but anonymous career as a commercial designer. He continued making sculpture on the side, focusing on sculptural busts in terracotta and carved stone, working in a studio behind his house in the Cleveland suburb of South Euclid.

Claude Conover quietly went about his business for decades, creating some of the century’s best ceramic artworks...

And then, in 1959—at the age of fifty-two—he made a pot. “I really don’t know why I did it,” he later said. “I was wedging a large piece of clay and the shape just seemed to suggest a jug.” Ungainly but striking, the finished composition featured a roughly trapezoidal body, upright square spout, and a thick handle. It has the lines of an ancient Mediterranean ewer or, for that matter, a sculpture by Constantin Brancusi or Henry Moore. It also bears comparison to the contemporaneous work of Leza McVey, who had established a studio in Cleveland in 1953, immediately after graduating from the Cranbrook Academy of Art. (Conover was friendly with her and her husband William, a sculptor.)

Conover called his strange and beguiling jug Pottery Form A, and submitted it to the May Show, the premier event for the crafts in Cleveland. Presumably to his surprise, it won a purchase award; it remains in the Cleveland Museum of Art today. He began making pottery seriously, regularly submitting his vessels to the May Show, and just as regularly winning prizes there. Even so, it took a few years for him to commit himself entirely to ceramics. As late as 1966, he was still holding down his day job in commercial design, finding time in the studio on evenings and weekends.

“I think of it in terms of mass and volume instead of looking at it symmetrically like a potter does,” he would later say. “I never studied pottery so I didn’t start out confused.”

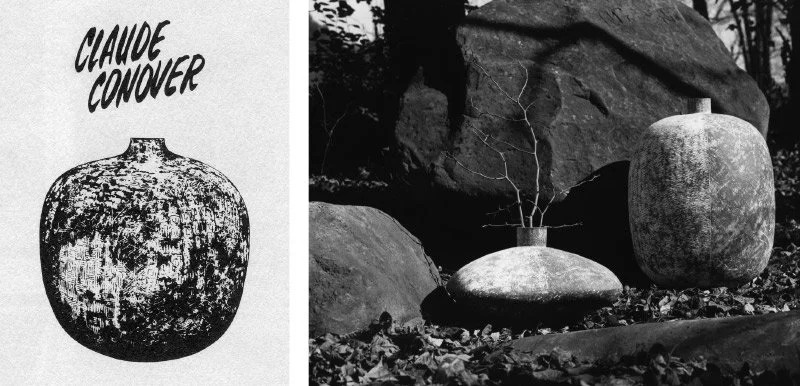

By this time, though, he had made huge strides in the medium. He had begun mixing his own stoneware clay, and more importantly, invented a totally unique way of constructing his pieces, informed by his work as a sculptor. “I think of it in terms of mass and volume instead of looking at it symmetrically like a potter does,” he would later say. “I never studied pottery so I didn’t start out confused.” Conover first laid strips of clay into curved plaster molds to create two matching hemispherical or semi-ovoid shapes. Then, he joined these concave halves together at their rims, creating a complete round object (though he probably was unaware of it, this part of the process was similar to that used in creating the famed “moon jars” of Choson dynasty Korea). He then covered the whole surface in a custom-made white slip, paddled the vessel into its final shape, cleaned and smoothed the interior, and added a foot, spout or a neck. Finally, he added texture, using his own handmade tools, including altered flatware and rollers fabricated from bisque-fired clay.

The objects resulting from this ingenious process have an austere beauty that transcends place and time. They are chalky and weathered-looking, suggesting some archaic, perhaps archaeological point of origin—an association that Conover encouraged by giving his pieces Mayan names, from Aaltan to Zopotec. (This practice began in 1964 with a work called Mitla, shown at an exhibition in Columbus sponsored by the Beaux Arts Club and the Columbus Gallery of Fine Arts.) He chose the titles out of a dictionary of about 800 Mayan words and, when he ran out, simply used them again, so that the same titles recur four or five times over the course of his career. Conover’s only known trip outside of the United States, besides Canada, was to Mexico, to view pre-Columbian ruins and museum collections. This interest, which may have initially been prompted by a visit to the 1959 exhibition Art of the Ancient Maya at the Detroit Institute of Art, was unusual among American ceramic artists at the time. Their peers in weaving (figures like Anni Albers and Lenore Tawney) studied ancient Peruvian textiles and more recent Mexican serapes, but potters were far more likely to adopt Japanese ceramics as a useful model.

“I do not believe the artist should try to make a profound statement or explain his work,” he said. “The object must speak for itself.”

Conover’s attraction to culturally distant artifacts (which, to his credit, never verged on problematic appropriation) says a lot about his aesthetic sensibility. He himself said little about this—he was a man of few words, as far as his own art was concerned. “I do not believe the artist should try to make a profound statement or explain his work,” he said. “The object must speak for itself.” Of course, this itself is a statement, and potentially a profound one. What may seem like Midwestern reticence on his part happened to coincide with the dominant position among modern abstractionists, including in ceramics. Many, like Conover, were drawn to ancient and so-called “primitive” art—not for its cultural content, but purely for its form. A good example is Hans Coper, the revered British ceramic artist, who was far younger than Conover but worked concurrently with him. It was ancient Mediterranean vessels and sculptures that captured Coper’s imagination; he too invented novel means of hand-building and altering his work, which was sheathed in subtle texture and monochrome slip. And he professed a similar distrust of interpretation: “One is apt to take refuge in pseudo-principles which crumble. Still, the routine of work remains. One deals with facts.”

This comparison may startle, given the difference between Coper and Conover’s milieus. And indeed, there was a world of difference between Coper’s London—where he worked alongside the refined and cosmopolitan Lucie Rie, like him an émigré from Central Europe—and Conover’s suburban studio, an altogether more prosaic setting. Yet it would be a mistake to underrate the vitality of Cleveland’s craft scene. Though it has received far less scholarly attention than Voulkos’s circle in California, this context was arguably just as dynamic and innovative, especially in the 1960s. In addition to the aforementioned Leza McVey, the city was then home to Toshiko Takaezu, another recent graduate of the Cranbrook program, and arguably the greatest exponent of Abstract Expressionism in postwar ceramics. It was in Cleveland, in 1958, that Takaezu created her first “closed forms,” which have parallels to Conover’s work in their assured enveloping of space. The city was also a center for metalwork and jewelry—the leading exponents being John Paul Miller, Frederick Miller (no relation), and the enamellist Kenneth Bates—and the studio glass movement was born in 1964 in nearby Toledo, and pioneered locally by Edris Eckhardt.

Just as important as Cleveland’s extraordinary talent were its superior opportunities for exhibition, a legacy of the Arts and Crafts era. In addition to Conover’s annual award-winning presentations at the May Show, he exhibited his work at Potter & Mellen, which was in its day a peer of Gump’s in San Francisco or Tiffany’s in New York City. Founded in 1899 as a venue for fine jewelry and metalsmithing, by the postwar era it had branched into other wares, including ceramics. Conover was able to show and sell his work there regularly. This was a typical venue for him; at a time in history when craft was mostly sold in stores, not art galleries, he presented his work mainly at regional exhibitions and retail establishments across the Midwest: towns like Akron, Canton, Detroit, St. Paul, Wichita, and Youngstown. He was quite literally a journeyman, whenever possible delivering his work in person, in the back of his Ford. Conover did have some presence in museum exhibitions, too, showing in the important Ceramic Nationals in Syracuse, and at university art galleries. He also had relationships with a few of the ambitious craft galleries that emerged in the 1970s, like the Hand and the Spirit in Scottsdale, Arizona, and Fairtree Gallery, in New York.

Revolutionary breakthroughs, self-consciously radical and purposefully disruptive, do much to shape the course of art history. More often than not, though, it’s people like Conover who give it substance.

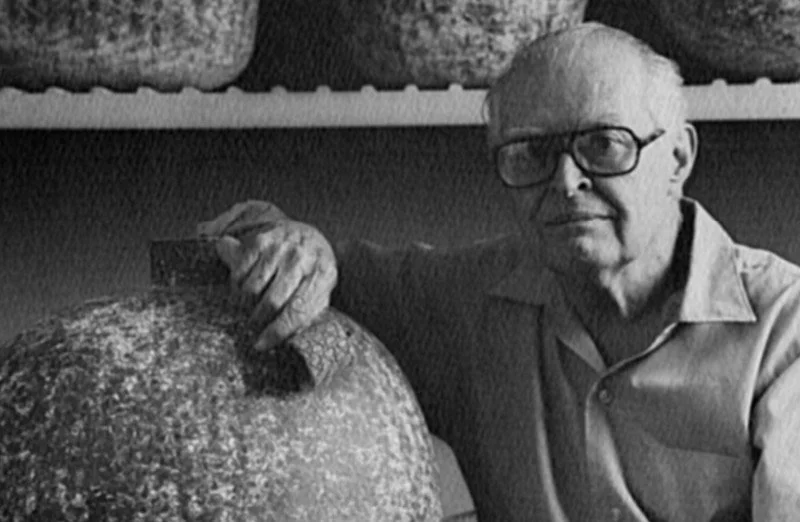

As all this suggests, Conover was definitely no elitist. He was also incredibly prolific. Working entirely by himself, he made as many as eight pieces a week at the height of his production in the 1970s. (He deserves to be remembered, among other things, as the hardest working man in American ceramics.) They were priced relatively affordably, too, $150 or so each. This populist approach, in combination with the sheer monumental presence of his work—its “stony surfaces and calm symmetry,” as one reviewer aptly put it—gave Conover an interesting position within the studio craft movement. In 1964 the magazine Craft Horizons, under the editorship of the redoubtable Rose Slivka, published a “pictorial compendium” of 327 of the nation’s leading makers. (This was timed to coincide with the first conference of the World’s Craft Council, held in New York City.) Slivka explained that the American craft movement was divided into two groups: artist craftsmen, “those make one-of-a-kind objects of superb aesthetic quality— who produce objects first to please themselves,” and production craftsmen, “engaged in the design and execution of each object in volume,” for a widespread market. Conover, who was included in the survey, fit both descriptions perfectly.

A Claude Conover vessel at the inaugural Objects: USA exhibition in 1969.. Lee Nordness business record and papers, circa 1931-1992. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

For the next twenty-five years, until he finally retired in 1990 at the age of 83, Conover stayed this complex course, making it look entirely straightforward. While vessels of near-spherical and ovoid shapes continued to make up the vast majority of his output, he did innovate new forms, including totemic stacks, in which multiple volumes are vertically superimposed (a compositional format that Voulkos too explored in these years, interestingly), and what he called “bottles,” upright vessels with gracefully tapering necks. To surface the pieces, he devised a panoply of subtle nuanced textures, sometimes unifying them with an all-over treatment, at other times articulating their amplitude through horizontal scoring. A career high came in 1969, when he was included in the seminal exhibition and catalogue Objects: USA, the definitive survey of the American craft scene. A low came a few years later, when he lost his whole studio to a kiln fire. His grandson, Jim Boehnlein, recalls the scene: “I remember standing next to my grandfather gazing with him at the smoldering wreckage. I could tell that he was devastated by the loss, but I don’t remember him saying a word. Knowing him, he likely was already starting to think about how he would re-build, which he did during a short period of time.”

That seems a quintessential picture of this outwardly unambitious, incredibly accomplished man. Claude Conover quietly went about his business for decades, creating some of the century’s best ceramic artworks, and never making a fuss about it. That he was so unassuming should take nothing away from his achievement. Indeed, it should probably enhance his stature in our eyes. Today, many in the art world—an art world, incidentally, in which ceramic is at last being accorded a status equal to other disciplines—are looking for ways to democratize. To abandon pretention and exclusivity. To reach a broader public. Conover may seem an unlikely role model in this context, but that is exactly how we should see him. Revolutionary breakthroughs, self-consciously radical and purposefully disruptive, do much to shape the course of art history. More often than not, though, it’s people like Conover who give it substance.