Desire Ex Machina

Published in the exhibition catalogue Beautiful and Grotesque, Cleveland Institute of Art, 2019.

“My cache of penis bones is running out.” That’s a snatch of studio conversation, not all that atypical, with the artist William Harper. It’s often said we live in a turbulent age, an age of extremes. But the tumult of 21st century life has nothing on Harper’s imagination. It’s a jungle in there, an enchanted one, filled with hidden treasure. Each of his objects contains multitudes, and vibrates with contradiction: beautiful and grotesque, yes, but also lurid and luxurious, figural and abstract, fragmentary and gestural, heroic and absurd.

The penis bones, which used to belong to raccoons, are among the many specimens that Harper collects and incorporates into his jewels. They happen to be particularly revealing of his aesthetic. The bones seem botanical at first, uncurling attenuated and elegant like young palm fronds. When you find out what they are, there’s a shock – somewhere on the spectrum from fascination to disgust, depending on your proclivities. Harper is ever on the hunt for these moments of dissonance, and the psychological depth charge they can detonate. For all the gorgeousness of his pieces, they always radiate a dark power, drawn from the deep well of his subconscious. It seems apt that his materials come from places normally unvisitable: bones, from the inside of animals; stones and metals, mined from the earth’s crust; shells and coral, dredged from the bottom of the sea.

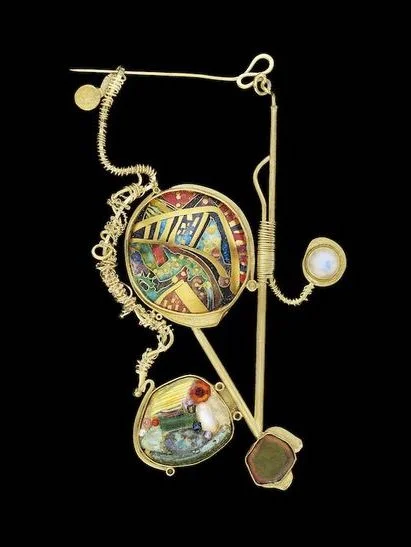

"Faberge's Ashanti Beads,'' 1994.

Harper has forged an idiom entirely his own. It’s hard to think of another artist who fuses the precious and the sordid so completely. Four hundred years ago, though, it was another story. Artists of the baroque era dwelled luxuriantly over such opposing energies. Key to their thinking were the principles of alchemy, by which matter was transmuted (the part everyone remembers today), but also infused with symbolic meaning. Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s orchestration of inert naturalia into lifelike heads; the intensely controlled yet totally excessive workmanship of court goldsmiths; Caravaggio’s juxtaposition of divine revelation and dirty peasant feet: all were expressions of the baroque instinct for intertwined opposites. One could even say that this period saw the emergence of a particular definition of mastery, as the ability to integrate seemingly irreconcilable things.

That is Harper’s kind of mastery, too. He has performed synthetic magic throughout his career. His way is to take up a subject, or invent a story or an alter ego, and then pursue the idea obsessively until a body of work has manifested itself and his curiosity is finally exhausted. This can take years. Often, he will realize a fragment of a piece – say, a juxtaposition of a concentrically banded tourmaline with an accompanying passage of enamel – and then lay it aside, awaiting further work. Perhaps because of this habit, his final compositions are like extended itineraries. One dramatic incident leads to the next, sometimes in a tight circle, but more often in a series of branching pathways.

The meandering journeys thus described are to some extent, biographical – the stories are always Harper’s own. He sometimes portrays himself allegorically in his work, typically in the guise of an alter ego. A seminal example is his brooch Self-Portrait as Saint Sebastian, which he decodes like this: “it has everything an artist needs: an eye, to look out into the world and see what is there to work from; an inner eye, where you assimilate; emotion, through the blood and body; and finally an arm full of nails, as society often rejects us.” Another self-depiction, this time as Saint Anthony, features a single cyclopean eye, which Harper retrospectively saw as prophetic of eye problems he suffered a few years later.

“Royal Barcelona Dubu.”

Still more personal is the libidinous register of the work. Harper is bisexual – he has an ex-wife, two children, and a much-loved husband – and he is extremely interested in the dynamics of unbounded desire. This is another thing he shares with the old alchemists: their fascination in hermaphrodites, of a soul that can find gratification in any body, even its own. He’s even written a porn novel, aptly entitled Caravaggio’s Closet. (It’s yet to be published – sorry.) Sexuality hides in plain sight in Harper’s work, much as queer identity was obliged to do in American culture until recently. He is delighted by the tacitly phallic forms of irregular baroque pearls and crystal shafts, and has also built works around stones or enamel gems that are clearly vaginal, if you choose to look at them that way. On a still subtler level, the way that his jewels give themselves internal chase can be seen as a metaphor for the body’s erotic drives. To the extent that Harper’s works function as self-portraits, they show him as “polymorphously perverse,” as the psychiatric establishment used to put it. Or, as we might say today, up for anything.

Harper adopts the same stance, come-one-come-all, to cultural quotation. While the spikes in his aforementioned Sebastian brooch do refer to the saint’s martyrdom by arrows, they also are based on the nails driven into Nkisi figures made by the Kongo people of Central Africa. In fact he is particularly knowledgeable about African art, having collected it for many years. But he also draws from a range of other sources: Oceanic carvings, medieval metalwork (both Byzantine and Latin), Indian textiles, the architecture of Gaudí, and contemporary art. This truly multiple multiculturalism flies in the face of some contemporary sensibilities, which would ask us to police boundaries of appropriateness based on some imagined standards of cultural ownership.

Harper totally rejects this territorialism. He got his aesthetic education in Cleveland, which has not just a leading art school but also one of America’s great museums, with a collection ranging over vast tracts of time and space. Certainly, he is aware that the history of such collections is bound up with colonialism and violence; but he is equally aware that to close down some avenues of inspiration would be to deny his own authentic sense of self. Indeed, his omnivorous appetite transcends visuality itself. He is one of those rare people who experience synesthesia, by which sounds seem to take on color, color takes on smell, and so on. Mahler, for him, is not like an abstract painting – it is one.

It makes perfect sense that Harper would navigate the world in this way - that experiences which seem discrete to most of us would, for him, merge into an undifferentiated whole. The jewels he makes offer many pleasures. They are intricately made, perfect specimens of the goldsmith’s craft. They are compositionally complex, built around a unique sense of line and rhythm. And they tell compelling, multilayered tales, rich with humor and insight. But the most important thing about Harper’s works is the palpably personal sense they give of its creator. Each is a flash of illumination into his particular way of looking at the world - a sprawlingly capacious vision, somehow compressed into a thing that can be hung on the body, or held, spellbindingly, in the hand.

“Flotsam I.”